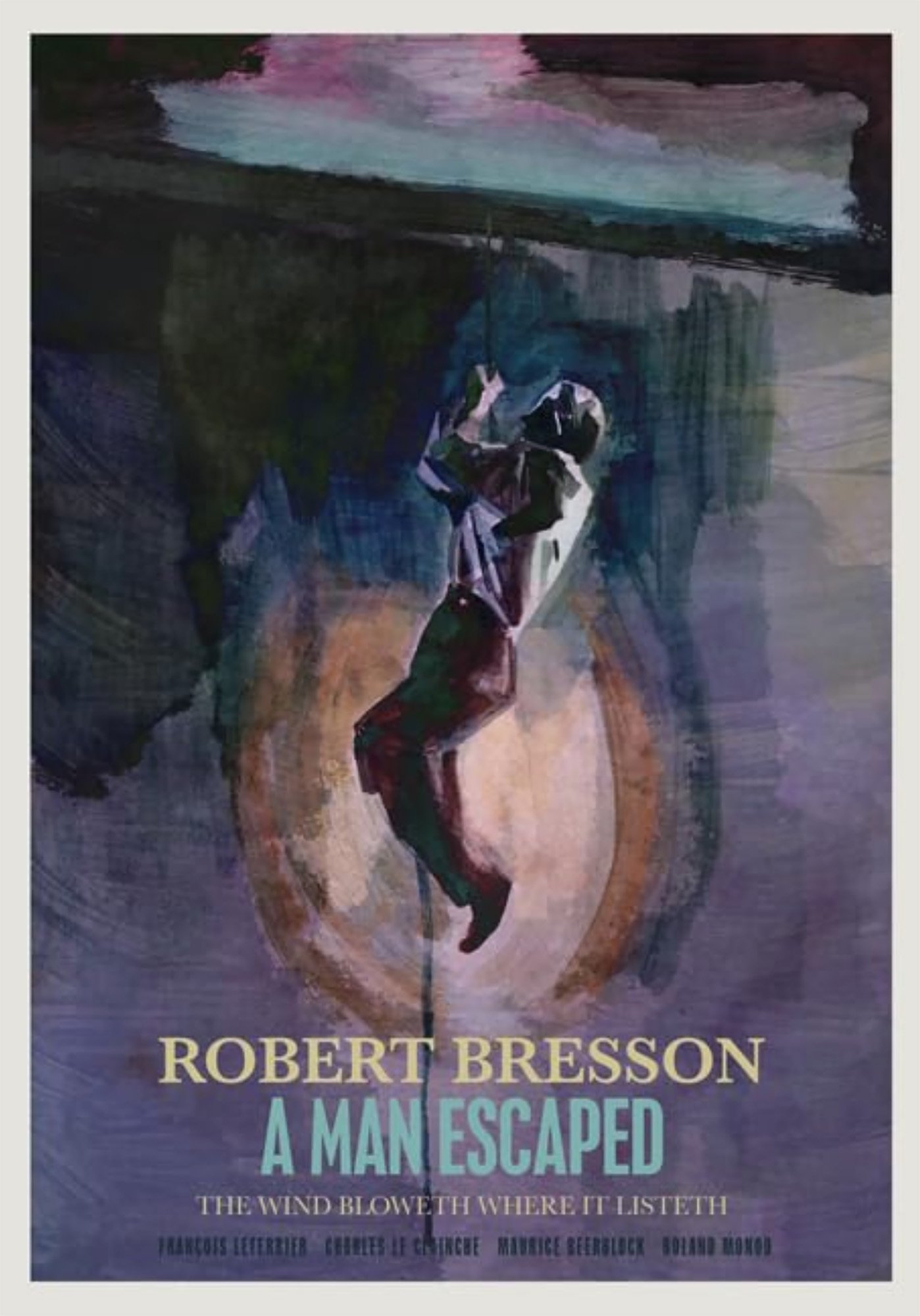

Sound of a shot

Moviesound Unplugged

How early movies put sight and sound together

NEW STUFF: WE HAVE A SPOKEN WORD VERSION OF THE BACKGROUNDERS FOR THIS EXCELLENT MOVIE. LISTEN UP!

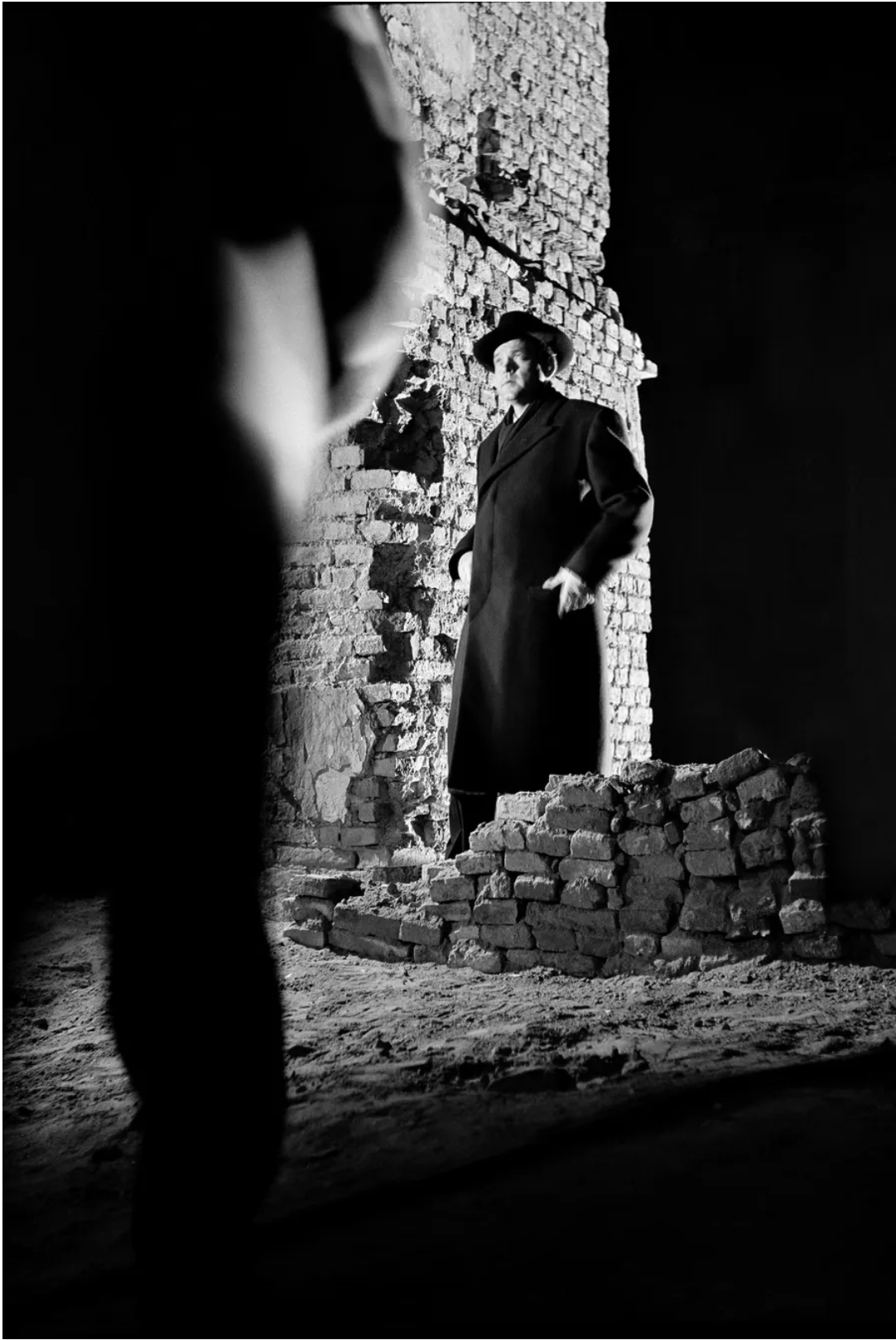

There are cinematic treasures to be explored where sights and sounds play together in artful ways you may not have imagined.

Before the modern movie experience of sound,

directors and film editors had to make choices about what

the audience would see on the screen and hear on a single speaker.

How they organized one strip of film images to go with a few more strips of recorded sound pieces could make or break

an old-school movie mix. The most entertaining and artful sound jobs would succeed at telling a story effectively.

Our selected movie clips of classic films (without the complication of the hundreds of carefully edited sound elements)

are shown as Video Sound Tours, with graphics that explain what to listen for.

We have also written extensive downloadable Backgrounder Blog pieces, (both written and spoken word audio) about the movies and the people who made them.

Welcome to

Sound of a Shot

Here’s a trailer…

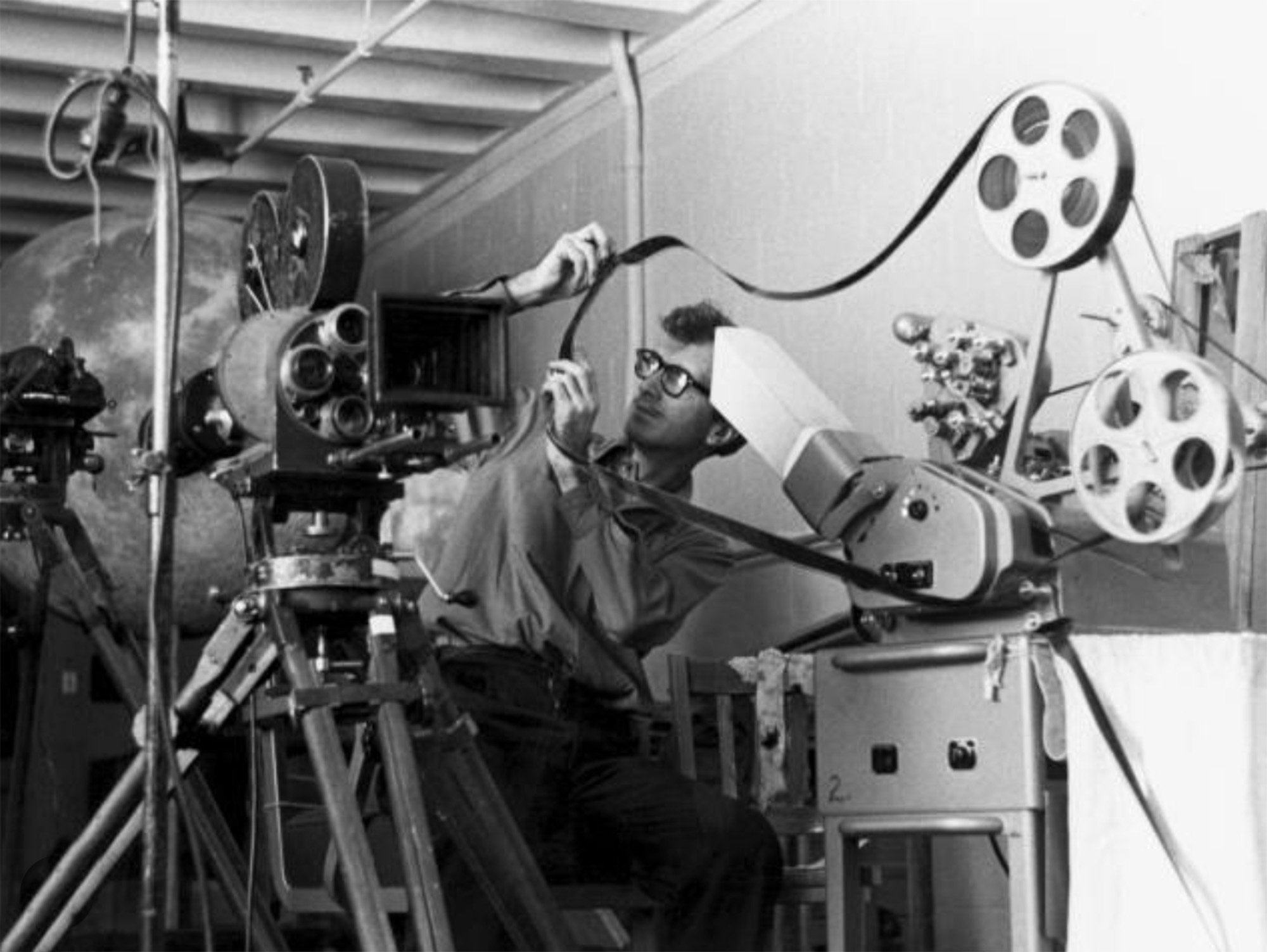

Antique two-gang film synchronizer, seen on E-Bay

“

The most entertaining and artful sound jobs would succeed at telling a story effectively.

”

Sound Design is not necessarily the name of a job.

It is a phrase that describes a standard of complementary aesthetic and technical qualities: the intelligent and deliberate organization of smaller elements of live and recorded sound, into a coherent and powerful form of communication.

Our selected movie clips of classic films (without the complication of the hundreds of carefully edited sound elements) are shown as Video Sound Tours, with graphics that explain what to listen for. We have also written extensive Backgrounder Blog pieces about the movies and the people who made them.

Moviesound Unplugged

Everyone who works with sound (or music) is acutely aware of ear training and critical listening skills. Making movies with sound has complications which never could have interfered with Silent Cinema. Movie sound workers are charged with being an equal part of the storytelling process. We have to at times define, enhance, and clarify the text of a story that’s told by the edited stream of moving visual images. Sometimes we can provide counterpoint with a sound cue that is meant to undermine or contradict the visual story.

-

Contemporary and late 20th Century movies are built from complex mixes and sub-mixes (predubs) necessary to build the dramatic impact audiences expect from digital high-resolution multi-channel surround sound. Students can get access through the web to materials that demonstrate how popular blockbuster movies are prepared for a mix. These are fascinating, and there’s nothing we can add to that canon of sound study.

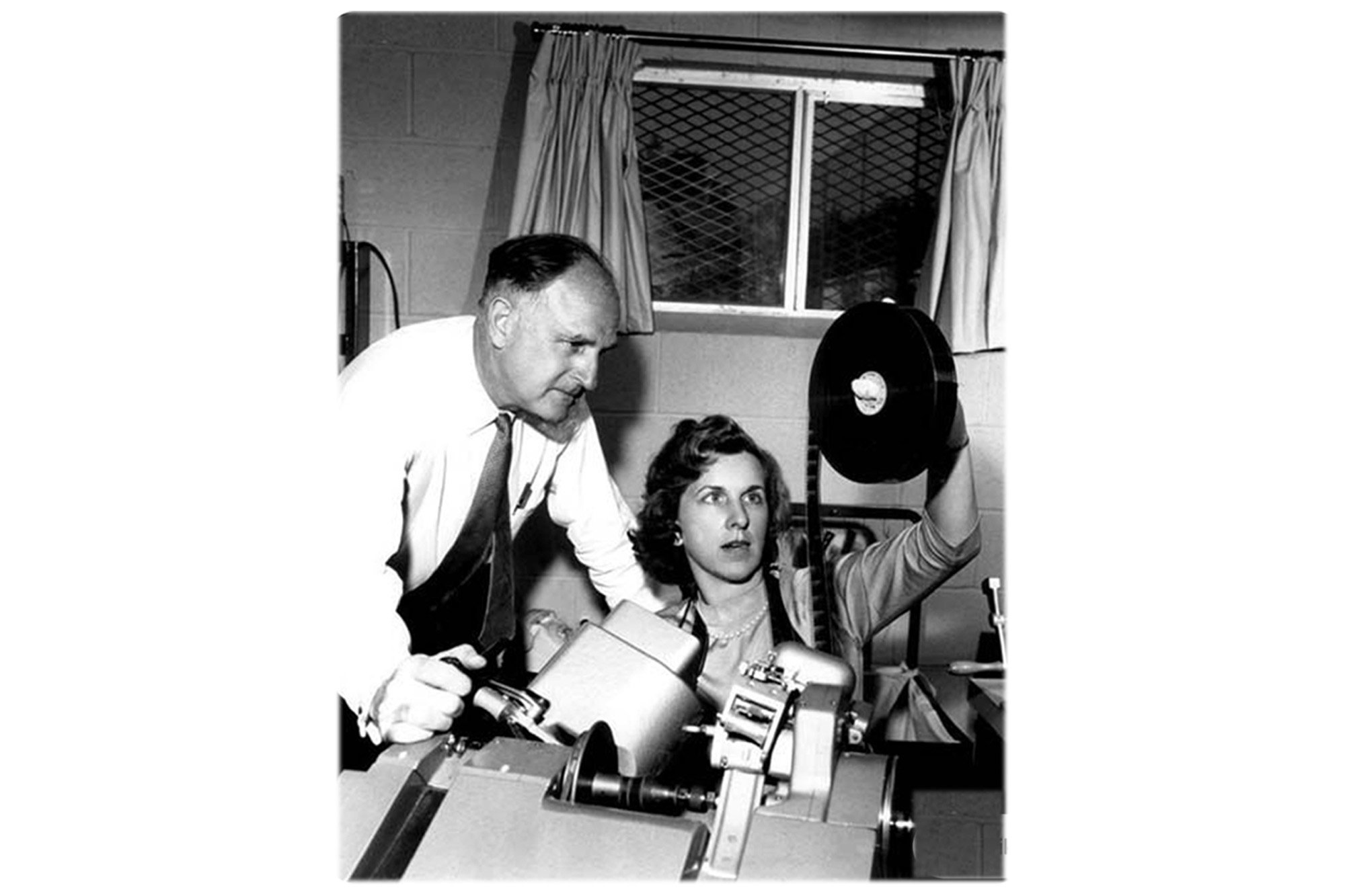

By comparison, previous generations put just a handful of audio pieces together for studio mixers to handle, and this could occur in the film editing process, well before the specialty artists called sound editors and sound designers existed. These elegantly simple decisions were made by the collaboration of directors and film editors in the process of making a first cut; And then just a few refinements could be made to the tracks before a final mix. While we enjoy the breakdown analyses we see of modern 5.1 and Atmos mixes and their editorial preparation, no such learning material exists for the first half-Century of sound movies. We draw on our experience editing movie soundtracks, and on critical listening, to make informed speculation about what the directors and film editors had in mind when they put track and picture together.

-

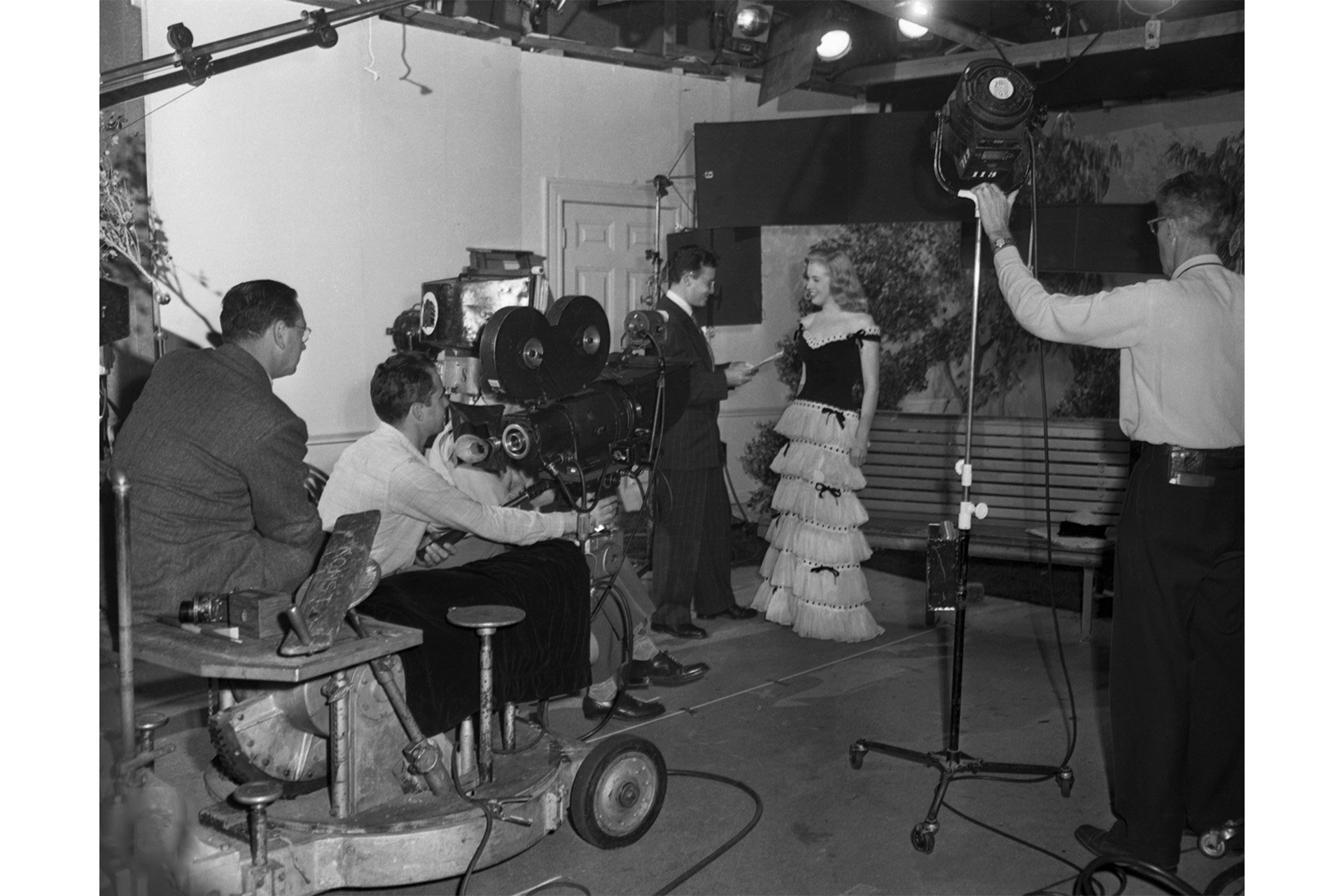

The art of Silent Cinema was still evolving when the first attempts at mass-marketing sound films interrupted their history. But sound film technology could not work smoothly without some new ideas about craftsmanship. The early Sound-on-Disc systems resisted editing and mixing. When optical Sound-on-Film systems developed (picture and track had near-perfect synchronism and pretty good audio quality in theaters), the simple editing of the picture exposed the noisy, chunky audible collision of recorded tracks.

Filmmaking crafts had to learn, through the ‘Thirties decade, to replace discontinuous chunks of sound with the same kind of fluid motion that had made the silent camera become virtually an Omniscient Eye. We had still to invent the Omniscient Ear, and that was never a matter of technology. Students understand that the early sound films had to isolate the camera and operator in a hot, sealed room to allow for optimal sound recording outside of that proverbial sweat box, so the complicated movements that added grace and fluidity to Silent Cinema were impossible. What is exposed when we study the early Talkies is the obvious discontinuity of recorded dialogue. From shot to shot, we can hear the differences caused by each shot’s very different placement and distance of the microphone. New techniques of editing the optical tracks and mixing them would have to evolve before restoring anything like the silent camera’s fluidity. Good directing and clever editing could move a story along as well as possible, but it is fun to watch sound movies slowly mature over the decade.

This website we are calling Sound of a Shot has three fundamental parts:

First, we present our growing collection of Video Sound Tours, where we break down clips of old monaural films and analyze the simple sound elements we can hear in the final mix, which flow in and out of each scene in order to support the story.

Second, we have a collection of Backgrounders which detail some of the context of each movie, with observations about the people behind the scenes wherever we can gather such information.

Third, Sound of a Shot includes a personal blog by the author, a wild card of observation stimulated by the process of all this research and sound analysis.

Fans of old movies should enjoy this work in progress, and our hope is that viewers on our tour bus will get in touch via email as they feel the need to participate.

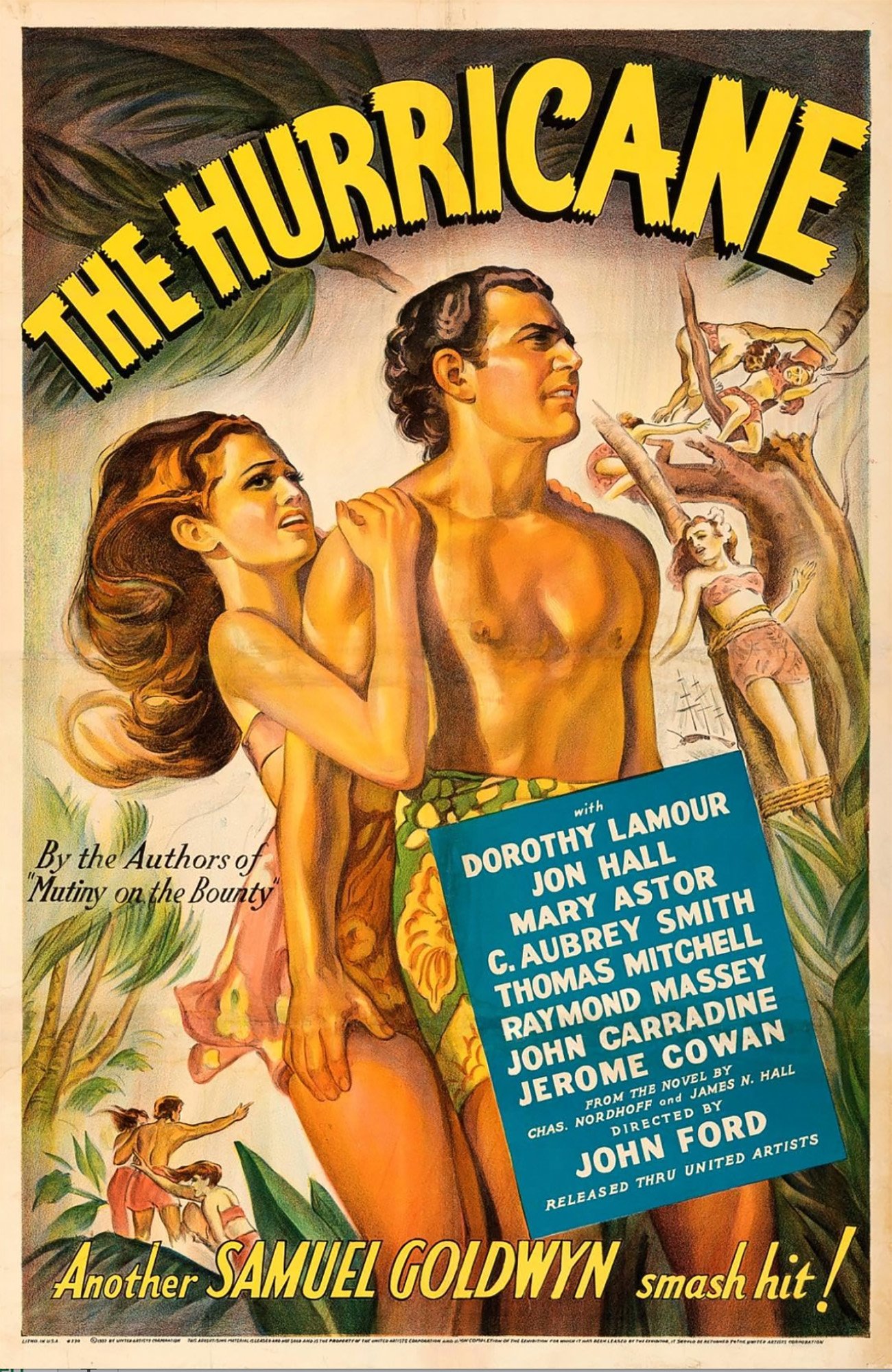

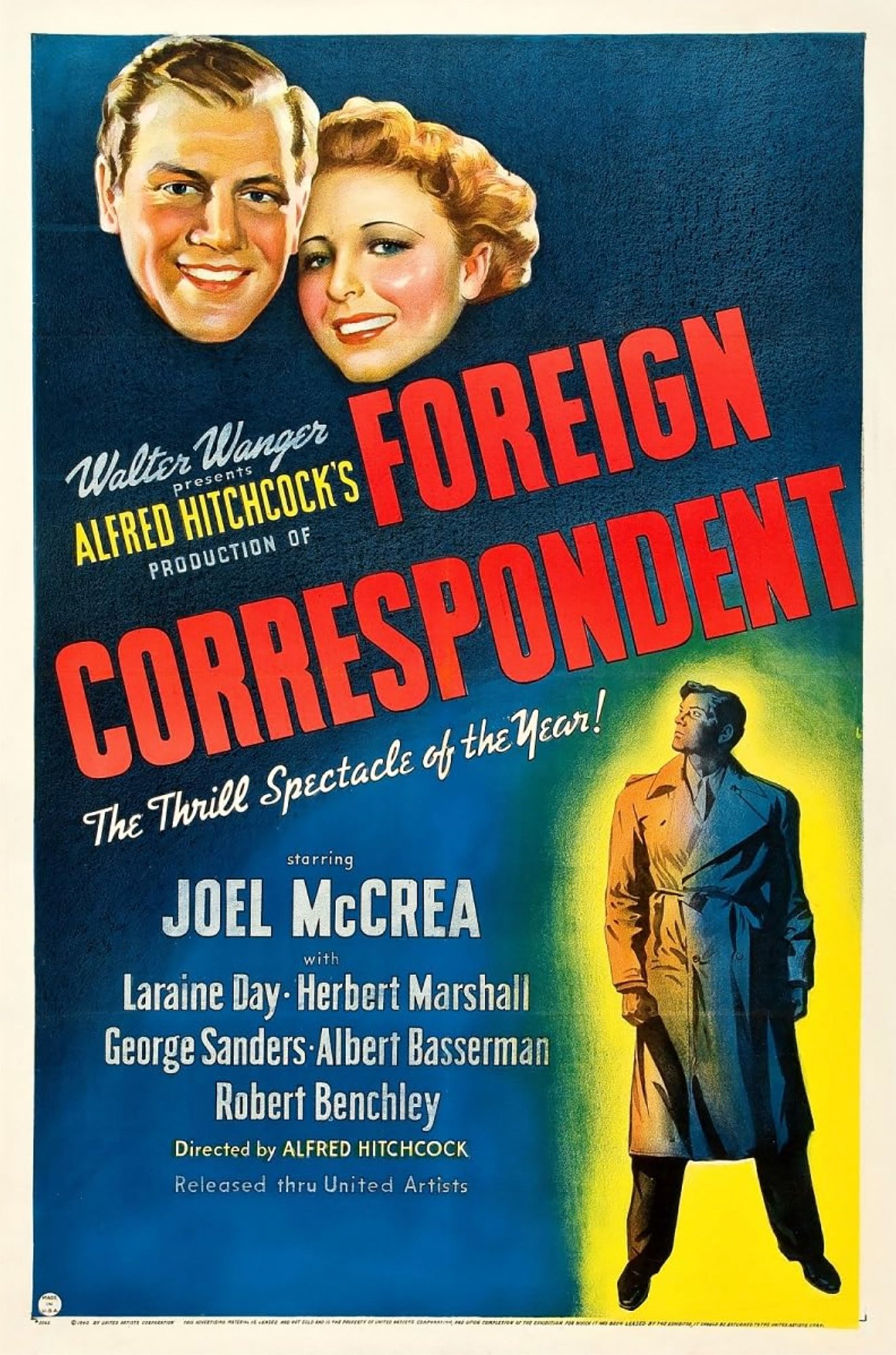

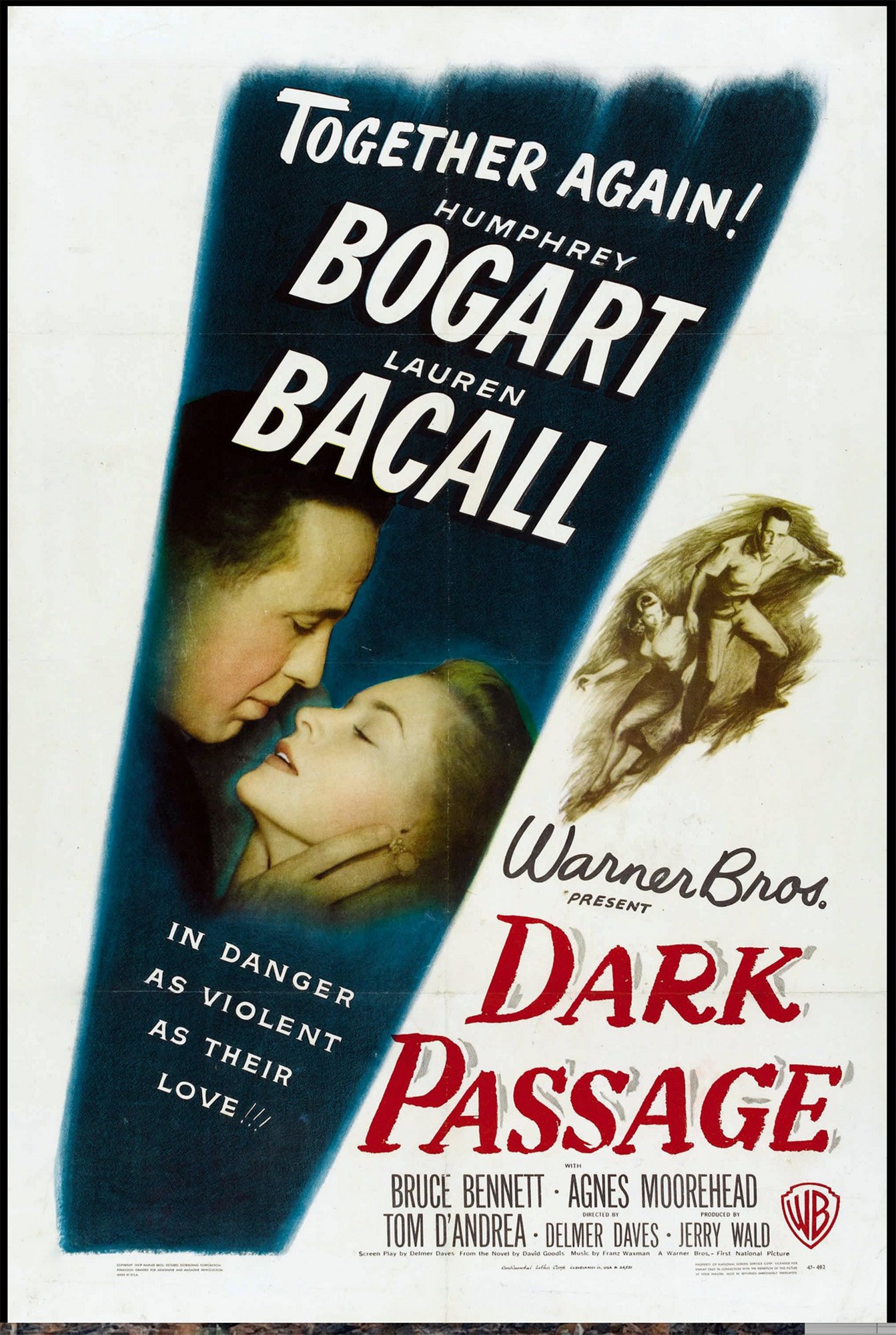

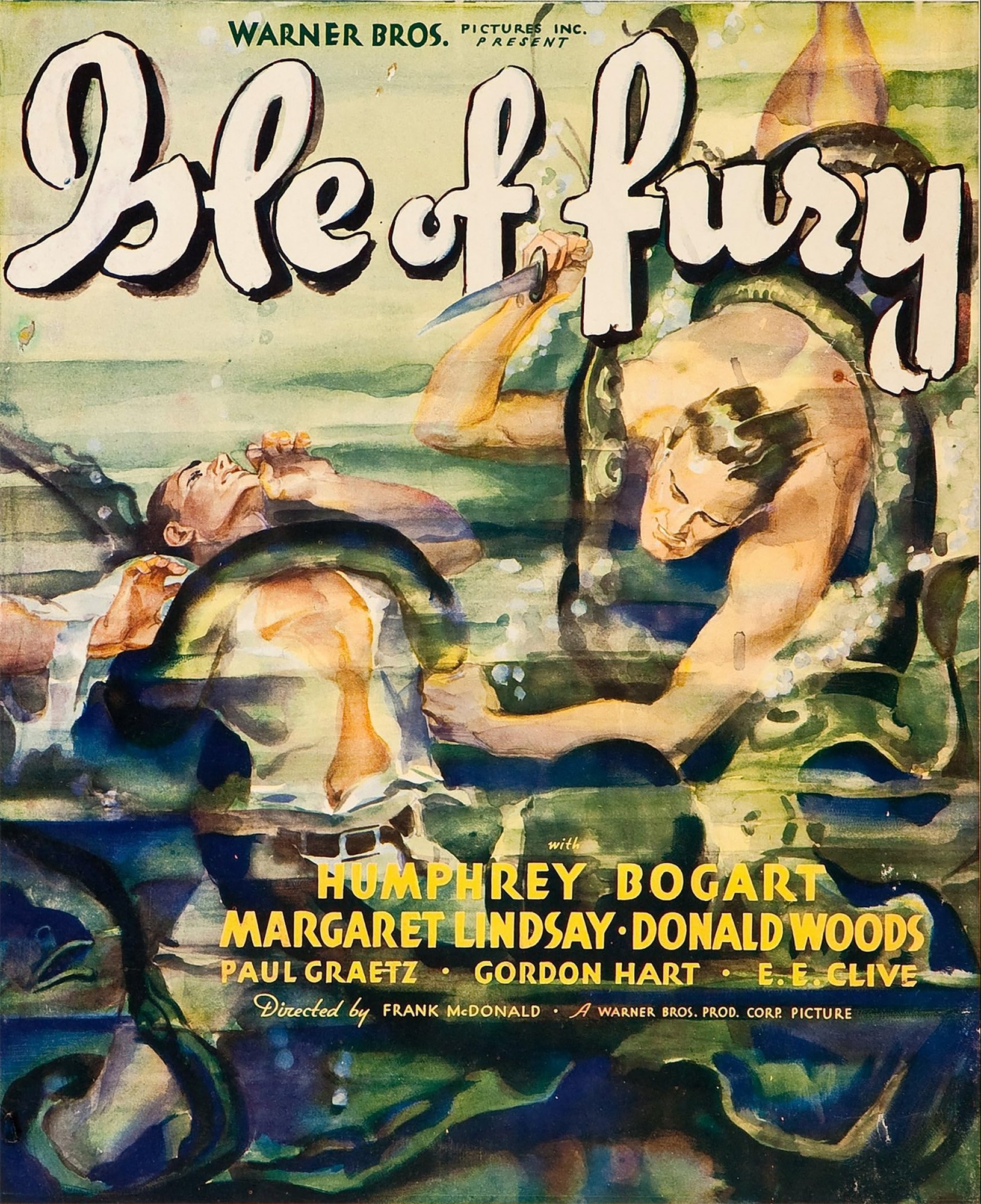

We don’t have Video Sound Tours of all these titles below as yet… but will be working on them.

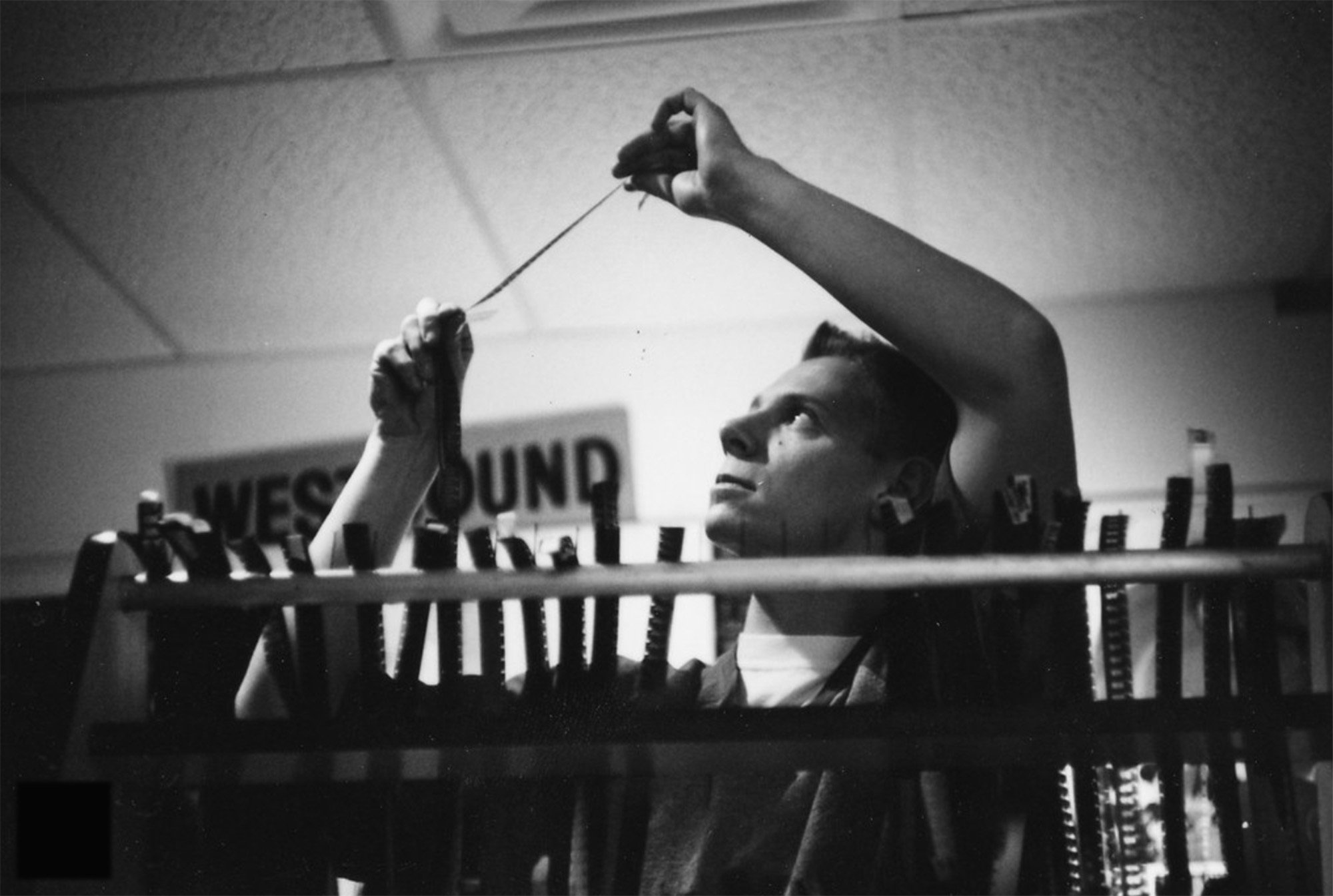

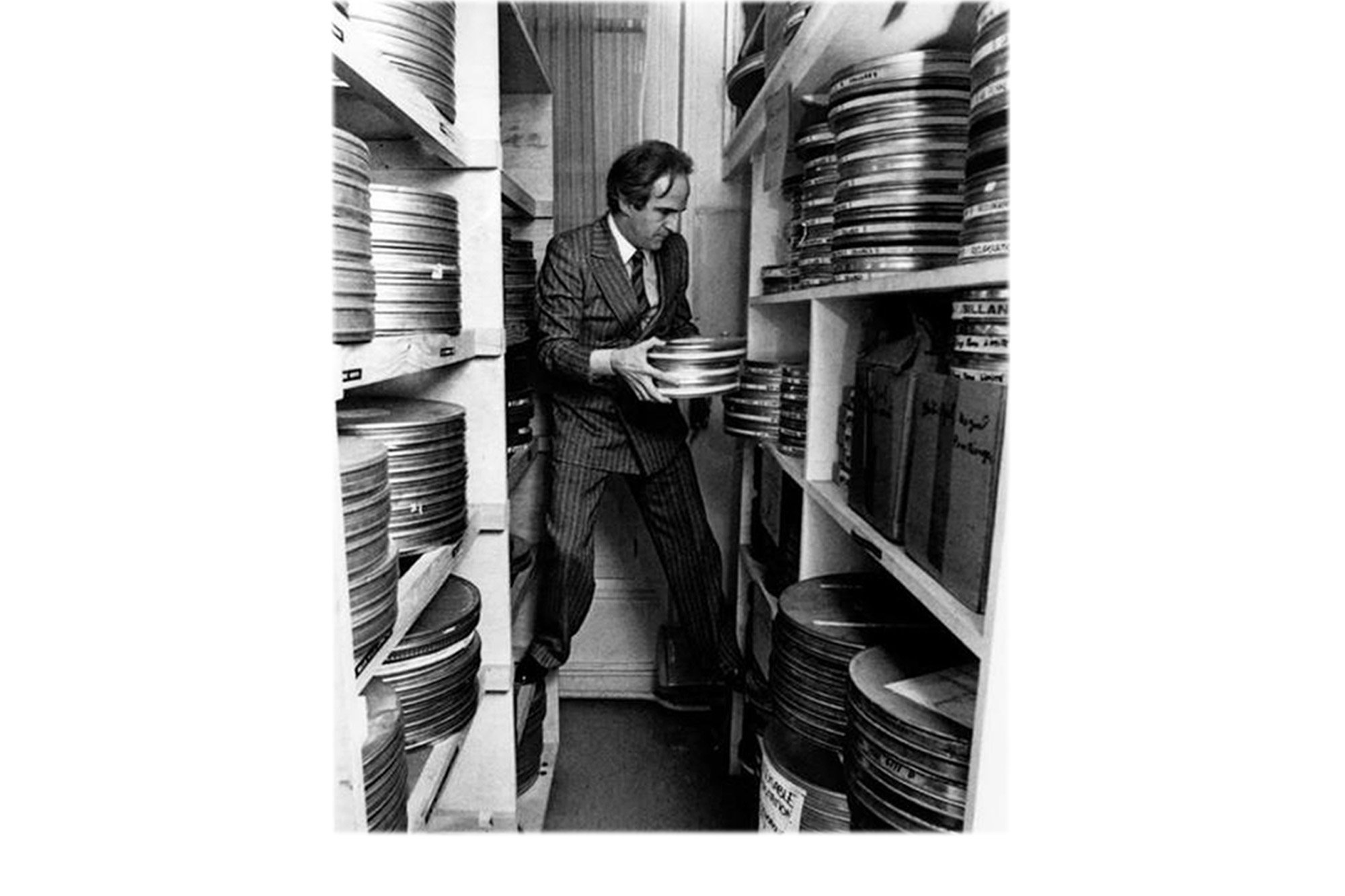

DS at Moviola, Hanna-Barbera 1978 photo by Mark Mangini

about

David Stone is a sound editor, a veteran of roughly 100 Hollywood feature films

and many television series.

Anyone should observe that we all live inside a media culture, and that young people listen passionately to the sounds of web videos, movies and games.

They have easy access to more powerful media-making tools

than any previous generation.

USE THE LITTLE ARROWS LEFT AND RIGHT OF THE GALLERY BELOW